Introduction

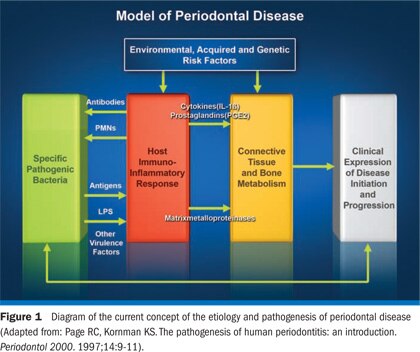

Until the 1970s, treatment strategies for periodontal disease were primarily based on the understanding that plaque bacteria and their products mediated the tissue destruction in periodontal patients. This concept began to change, however, when investigators reported that host responses to the causative bacteria were a major contributor to disease pathogenesis.With a new understanding of host response and periodontal disease pathogenesis, it became apparent that inhibition of certain host response pathways might be an additional strategy, in addition to suppressing the causative bacteria, for treating periodontal diseases. The current understanding of periodontal disease etiology and pathogenesis emphasizes the role of the host in tissue destruction (Figure 1).

Initial studies of host modulation

In the early 1970s, Paul Goldhaber and Max Goodson began to implicate arachidonic acid metabolites as important inflammatory mediators of the bone loss of periodontitis. The arachidonic acid metabolites include a variety of fatty acidderived compounds that are enzymatically produced and released in response to local tissue injury. These metabolites, such as prostaglandins, were implicated as major mediators of tissue loss in periodontal diseases because they are potent stimulators of bone resorption, are present in gingival tissues, and are elevated in diseased individuals.1,2

In 1971 John Vane and colleagues reported that aspirin and aspirin-like drugs, also called nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), interfered with the arachidonic acid metabolite pathway by blocking the enzyme cyclooxygenase, thus blocking the production of prostaglandins.3 Soon thereafter periodontal investigations began asking the question: "Might the blocking of cyclooxygenase with NSAIDs, thus blocking prostaglandins, have an affect on the bone resorption of periodontitis (Figure 2)?"4

Utilizing the beagle experimental periodontitis model,Nyman et al examined the modulation of arachidonic acid metabolites with systemic indomethacin and reported that the NSAID indomethacin, given by mouth, suppressed alveolar bone resorption and gingival inflammation in the beagle.5 Weaks-Dybvig et al studied the effects of indomethacin in squirrel monkeys with ligature-induced periodontitis and reported that animals treated with systemic indomethacin had significantly less alveolar bone resorption (height and mass) and suppressed osteoclast density as compared with control animals.6

Williams and co-workers were the first to report in vivo data on the effect of NSAIDs on the progression of naturally occurring periodontal disease in an animal model. Over a 12-month treatment period, the effects of the NSAID flurbiprofen (Figure 3) were compared with a placebo in aged beagles with naturally occurring periodontitis. The investigators combined experimental agents with conventional nonsurgical and surgical treatment modalities. Their results indicated that daily administration of 0.02 mg/kg flurbiprofen by mouth significantly decreased the rate of radiographic alveolar bone loss at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months in both surgically and nonsurgically treated animal groups when compared to baseline levels. The rate of alveolar bone loss did not decrease significantly over the treatment period for placebotreated animal groups.7

Other NSAIDs, either systemically or topically administered, also have shown efficacy in treating periodontal disease in animal models. The propionic acid derived NSAID ibuprofen at 4.0 mg/kg and 0.4 mg/kg (sustained release and standard by mouth formulations) was effective in blocking alveolar bone loss in beagles with naturally occurring periodontitis.8 Naproxen (2 mg/kg for one month and 0.2 mg for 6 months) reduced radiographic periodontitis progression in the beagles by 61% when compared to pretreatment levels.9 Williams et al also reported a 71% suppression in radiographic bone loss rates for dogs treated with a topical flurbiprofen-propylene glycol gel (0.3 mg/ml daily).10 Similarly, a topically applied substituted oxazolopyridine derivative reduced histometric bone resorption, as well as clinical attachment loss and gingival inflammation, in squirrel monkeys with ligature-induced periodontitis.11 Monitoring the effects of two topical NSAIDs, ibuprofen and meclofenamic acid, in cynomolgus monkeys over 20 weeks, Kornman et al reported significant inhibition in alveolar bone loss despite continuing signs of clinical gingivitis and plaque accumulation with either agent.12 Over a 16-week period, Howell et al evaluated the anti-gingivitis effects of topical piroxicam in gel and liquid forms (2 mg/ml) on gingivitis in the beagle dog.13 Gingival and bleeding indices were significantly reduced after 2 and 4 weeks in the piroxicam-treated dogs as compared with placebo controls; however, no significant differences in plaque scores among the groups were noted. The results of these latter 2 preclinical studies indicate that NSAIDs may act in the presence of significant local factors that would otherwise influence disease progression. Paquette et al have evaluated topical (S)-ketoprofen formulations in beagle dogs.14 Following induction of experimental periodontitis, 16 beagles were randomized for (S)- ketoprofen dentifrices (0.1%, 1.0%), (S)- ketoprofen capsules (10.0 mg by mouth), or placebo dentifrice and assessed radiographically over a 2-month period. A significant reduction in gingival inflammation was reported with (S)-ketoprofen treatments.

There are also compelling data from human cross-sectional and cohort studies indicating periodontal disease inhibition with NSAIDs.Waite et al evaluated the periodontal status among 22 subjects taking NSAIDs for arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis and 22 age-matched controls not taking such medications.15 Subjects taking NSAIDs had lower gingival index scores and shallower periodontal pocket depths than individuals not taking NSAIDs. In a retrospective cohort study, 75 patients who had taken aspirin or aspirin plus indomethacin for at least 5 years for arthritis had significantly fewer sites with scaling plus acetylsalicylic acid result in synergistic reductions in gingival inflammation, probing pocket depth, and clinical attachment loss.22

Join us

Get resources, products and helpful information to give your patients a healthier future.

Join us

Get resources, products and helpful information to give your patients a healthier future.